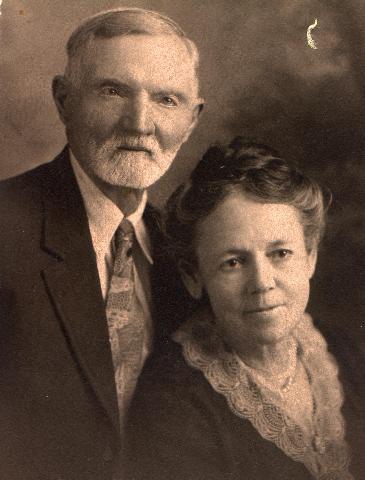

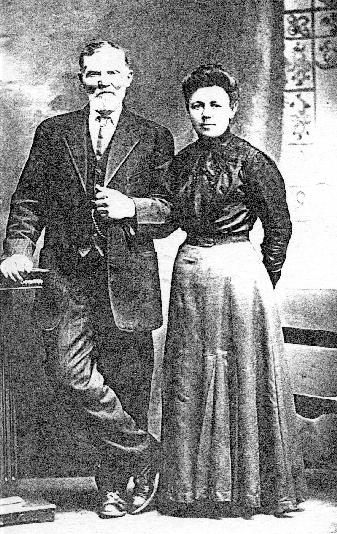

HISTORY OF SUSANNAH TITENSOR LARSEN

"A SKETCH OF MY LIFE AS NEARLY AS I CAN REMEMBER IT" My children have often asked me to write a few of the happenings of my early life. I was born January 7, 1855 in Manchester, England. My earliest recollections are of a large city where all was rush and roar. It was the city of Manchester, one of the largest manufacturing cities in the world. There I was born and lived until I was seven years old, when my parents decided to emigrate to America. On the morning of April 14, 1861 we bade farewell to home and loved ones, knowing we should never see them in this world again. It was a sad parting. I shall never forget the grief of my grandparents when they bid us all goodbye. On April 16 we sailed from Liverpool on an old sailing vessel called The Under- writer. We were five weeks on the sea, buffeted by the wind and the waves. After many storms and much seasickness we landed in New York and were taken to Castle Garden and kept until our baggage was inspected by the United States Officials. I can remember something of the trials and hardships of the Saints at Winter Quarters where we had to stay a month waiting for the ox-teams from Utah to take us across the plains. There were four families of us living In an old room and to make matters worse we children all had the measles. I also remember two young men being drowned while we were there. They were the only children of a widow. I shall never forget seeing them laid in the grave nor the sorrow of their heartbroken mother. She only lived to travel a hundred miles on the plains when she died. The Captain sent her body to be buried by the side of her two boys. The first Indians I ever saw came to our camp for food. The women and children were frightened to death. They thought they would surely be killed. I cannot remember all the details of that journey, I was too young, but there were some things stamped upon my memory that I can never forget. Many a night after we had made our beds upon the ground and were all asleep a thunder storm would arise and the wind would blow our tents down, drenching us with rain. The children would cling around mother's knee, hide our faces In her lap and cry until daylight. At some points of the journey the Indians were very troublesome, especially In the Black Hills. They would try to steal our cattle. All who were able had to walk for there were three families to a wagon and only women with young children could ride. I was allowed to walk in the afternoon with my father; in this way I walked many miles crossing the plains. One day the Captain warned all those who walked to keep together and not go too far ahead of the wagons for fear of Indians, for they had been threatening us. Another day I gave them all a scare, and myself too. The company had been camping at noon and as the teamsters were hitching up their oxen, the young people went on ahead as usual. I thought I was big enough to go along too. They tried to send me back but I would not go, so when they came to a stream of water they would not help me over, thinking I would wait for the wagon train. But I did not. I followed up the stream thinking I would find a narrow place to cross over, but did not. After going for sometime I thought of the Indians, became frightened and ran back to the road but could not see the wagon train. They had crossed the stream and gone on but not knowing this I ran back along the road thinking to meet them. Imagine my terror when after running back for a long distance I could see nothing of them. In the meantime Father had caught up with the crowd that I had followed. Upon learning that they had left me at the stream he became alarmed and with a number of other men came back to find me. They searched up and down the stream without success, of course, because I was running back down the road as fast as I could. At last they saw my footprints in the dust and by following them found me. A badly frightened child I surely was. We arrived in Salt Lake City In October, the exact date I have forgotten. We were taken to what was then called Emigration Square, near where the City and County Building now stands. Our boxes and bedding were unloaded and there we were left, not knowing a soul in the city and we surely felt we were homeless. Father got a tent somewhere and we lived in that until he got work. About two weeks after that he moved us up to Bountiful, having found some friends he had known in the old country. They were very glad to see us and wanted us to make our home there but Father was advised to go to Cache Valley, as men of his trade (he was a machinist) were badly needed there. Oh, what a desolate place Richmond was then. Just a small fort of about two dozen houses built close together for protection. All had dirt floors. Father bought a one room log house. The window had no glass, only a piece of white cloth tacked over It. Father made a bedstead, a table and some stools; and there we spent our first winter in Utah. In the latter part of March 1862, my little sister died. She had been sick for a long time and Mother could not get proper nourishment for her. (Everyone was poor in those days.) The night she died we had no light but that of the fire, which was very poor because the wood was so green. My little sister was the third person to be buried in the Richmond cemetery. Many a time we children have cried for bread but Mother had none to give. Only a dish of boiled wheat and a little milk. There was no mill in those days. Father helped build the High Creek mill in 1862 or 1863, I forget which. He also helped build the first thresher and the first spinning wheel. Quite a number of people had moved into Richmond by this time and they laid it out in city lots. Each man was given a lot to build on. It was while Father was moving our log cabin that trouble with the Indians broke out in Franklin. Every able bodied man in the county was called to go up there and help settle the difficulties, and only the old men were left to guard the women and children. We had an old empty shanty to live in while the log house was being moved, and when night came on Mother was very frightened in the open shack with her little children. She took us and went to stay with a neighbor whose house had not yet been pulled down. It was a terrible night. None dared go to bed for fear the Indians might slip away from Franklin, knowing the women were alone. The next event fresh in my memory is the grasshopper plague. Our crops were nice and green when they came. They were so thick in the air it looked like a cloud as they settled on the ground. It looked as though our crops would surely be eaten. My mother used to take all the children early in the morning and go to the field to fight grasshoppers. We would walk up and down through the wheat waving a rag fastened to a stick to keep them moving, but it seemed all would be taken. The President of the Church called on all the people to fast and pray from sundown one day until sundown the next. They held a fast meeting at ten o'clock. I remember it as though it were yesterday. At the close of the prayer the grasshoppers rose in a mass so thick it obscured the sun as a cloud. They did not light again, but left, and our crops were saved. This was a testimony to me that the Lord hears and answers prayers. I remember the first school I attended at Richmond. It was a log house with a chimney built in one end. The fireplace was the only heat we had. The seats were made from slabs with pegs for legs. There were no desks to work on. The teacher had a small table for his desk. On it was a small cowbell which he used to call school. He also had a rule nearby which he wasn't slow in using. If we drew a picture we were punished. I have had many a whack over the hand. What writing we did was on slates. There were very few books and we had to borrow from each other. We had a small primer that was published in Salt Lake City. It was called the Deseret Primer and contained about a dozen leaves. Most of the homes in Richmond were made of logs and the roofs of dirt, with mustard and sunflowers growing on the roofs. I used to herd sheep on the hillsides of Richmond day after day. My mother spun the yarn and wove the cloth to make our clothes. In summer we all went barefooted. In the winter a shoemaker used any kind of leather to make us shoes. Our hats were braided by our mothers out of straw called shakers. I remember Father helping to build the High Creek and Muddy mills. Before they were built our diet consisted principally of .boiled wheat, with segos for dessert. Whenever me got flour it came from Logan. For a time Father worked in Salt Lake City in President Young's woolen mills. We could not buy matches any nearer than Salt Lake City and they cost 75 cents a box so, of course, we did not always have matches. We would watch the neighbors and when we saw a smoking chimney we would take an old tin plate and beg a little fire to start ours. I watched the soldiers when they went up north to Battle Creek to fight the Indians. The mud was so deep it was up to the hubs of the wagons and the soldiers were walking in mud over their boats. I recall such gruesome incidents as an Indian beating a white woman. A white man shot him and the Indians wanted to kill the white man to go to the Happy Hunting grounds. It caused so much trouble that all the men in Cache Valley were called to settle it. (Related to Susannah Larsen's daughter. Hazel Larsen Trimble.)

dkrka@utah.uswest.net

10890 Bohm Place

Sandy, UT 84094

United States